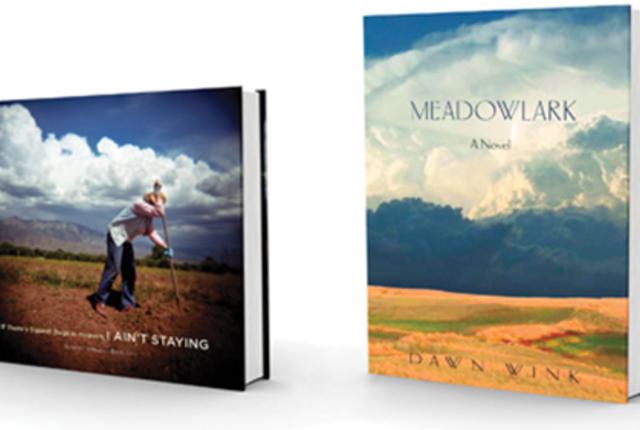

IF THERE’S SQUASH BUGS IN HEAVEN, I AIN’T STAYING: Learning to Make the Perfect Pie, Sing When You Need to and Find the Way Home with Farmer Evelyn

PHOTOS AND TEXT BY STACIA SPRAGG-BRAUDE (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2013)

Writer/photographer Stacia Spragg-Braude combines elements of memoir, biography, and local history in this compelling portrait of Corrales orchard farmer Evelyn Losack. Through example and homespun wisdom, Losack provides a powerful lesson in the meaning and value of place and community in the modern world. Anyone interested in fruit pies, indomitable characters, the struggle of family farming against encroaching urbanism, and whether an Indiana transplant like the author can plant roots and thrive in her adopted New Mexico will have plenty to savor in this fascinating book.

In the octogenarian Losack, Spragg- Braude finds her muse and mentor. A Corrales resident herself, Spragg-Braude chronicles their relationship and explores Losack’s family history in graceful words and revealing photographs. It turns out neither Losack nor that family story can be separated from the farm or the village around it.

The author meets Losack when they serve together on the village’s farmland preservation committee. Losack mentions to Spragg-Braude that she can’t keep up with the garden on her family’s 18-acre farm. Spragg-Braude offers to help. As the book unfolds, Spragg-Braude pitches in, working alongside the spry, tireless Losack in the seasonal round of farming chores and tasks. A New Mexico–style Renaissance woman, Losack can crack a joke, teach a village child piano, sing opera, and launch a vendetta on squash bugs—the bane of every valley farmer—in a seamless flow of relentless activity.

A former newspaper photographer with the now-defunct Albuquerque Tribune, and author of To Walk in Beauty (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2009), Spragg-Braude proves herself a capable reporter with an eye for the telling detail. With notebook, pen, and cheap Holga camera in hand, Spragg-Braude works alongside Losack on everything from planting, weeding, and picking to making tamales for Christmas and tending family graves in the local church cemetery. And don’t forget baking pies, a specialty of Losack’s, who has never met a recipe that couldn’t be fudged on the fly: “A few handfuls of flour here, some baking powder there, a fresh goose egg, why not,” the author writes.

Organizing the book by the seasons, Spragg-Braude pieces together a mosaic of stories and pictures that at first seem random, but then gradually spiral inward to reveal her own motivation: how she can become part of this place, too. You do that by giving yourself wholly to it, she decides, “plunging your arms up to your elbows in its soil, climbing its trees, letting your voice go in the wind. It’s about not forgetting who came before you and from where you came.” Under Evelyn’s tutoring-by-example, Spragg- Braude learns to embrace her querencia, a “connection to a place that cannot be severed.” She describes it as “the place your soul craves …. It may not be the place you were born, but it is the place where you belong.”

-CP

MEADOWLARK BY DAWN WINK

(Pronghorn Press, 2013)

In January of 1907, a young ranch girl named Grace received a gift from her mother, a journal for recording her various adventures. Four years later, 16-year-old Grace married a man named Tom and moved to his sod hut on the western South Dakota prairies. Her journal went with her. About 100 years later, Grace’s journal and her wedding dress find their way to her great-granddaughter Dawn Wink in Santa Fe, and so begins the true-life tale that wraps itself in and around Wink’s first novel, Meadowlark.

Wink, it so happened, had already begun a writing project based on the life of her great-grandmother and other ranch women who settled on the harsh Dakota prairies in the early 20th century. But deep into her research, her marriage and her life in Santa Fe crumbled. She shelved her writing and took refuge on the same South Dakota parcel, in the house Tom built for Grace, and where her own parents continue to ranch today.

Eventually, as Wink explains in the afternotes of Meadowlark, she returned to Santa Fe, determined to start over. But Grace, whose presence permeated the ranch house during her healing retreat, wouldn’t let her go. When the journal found its way to her, with what felt like Grace’s own blessing, she returned to her novel with fresh enthusiasm.

Meadowlark tells the story of a teen bride also named Grace. It begins on her wedding day, which quickly turns into an event that is anything but joyous. Her new husband is a brutal man, and he frequently abuses not only his young wife, but his dogs and horses as well. She soon discovers that she is only safe when he is riding far out on the range. She becomes a virtual prisoner in the dingy sod hut that has become her home.

Grace slowly makes friends with a half-Lakota widow and a young woman doctor who have both settled nearby. These friendships become her refuge as her life grows darker, her husband meaner. Life on the prairie was not exactly soft to begin with. As she and her neighbors battle grass fires and tornadoes, droughts and blizzards, she tries to bury her feelings and her soul in the hard work of the ranch. The raw beauty of her natural surroundings sustains her, when she is able to see it.

Wink’s historical research and family history pay off in Meadowlark, as the reader is immersed with great detail in the rugged life of a homesteading ranch wife. Although a contemporary sensibility seeps in now and then, the author creates a boldly honest internal narrative of a victimized woman without options. That Grace is able to survive—and eventually even find a kind of cautious happiness—is testament to the raw courage such a harsh life required.

-CV