El Rito, 14 miles south of Abiquiú, is a one-street village known for its history as one of Spain’s first New Mexico settlements. It's also home to a vibrant community of artists. And once a year, like a flower in the desert after a sudden rain, El Rito blossoms, beckoning visitors to its annual studio tour (elritostudiotour.org).

Like many of the villages that anchor northern New Mexico to the past, "El Rito has a beautiful history," explains Nicholas Herrera, an acclaimed santero who works with carved wood and handmade watercolors to create powerful bultos, retablos, altars, doors, and mixed-media pieces. All reflect the rich heritage and tradition of santero art, but with a wry political, satirical bent.

Herrera can trace his family back 15 generations in New Mexico and six in El Rito, and has meticulously documented his family's lineage and journey, which eventually brought them to Abiquiú and then to El Rito in the 1800s. "My family originated in the Canary Islands," notes Herrera, who sports a Pancho Villa–like mustache, and long hair worn in a braid down his back. "They were granted land by the King and Queen of Spain that had to be homesteaded for five years." Herrera restored the original log cabin and stone house on his family's ranch land in the mountains, and has lived his whole life in the El Rito village house that his grandfather built in 1890.

"This is where I belong," Herrera says. "I'm grounded here. When I go up to the mountains, I can walk where my ancestors worked and lived."

David Michael Kennedy is a portraitist and art photographer who creates stunning prints using the palladium method, a rare hand-crafted process discovered in the 19th century. His subject matter? Southwestern landscapes; celebrities like Bob Dylan, Isaac Stern, and Bruce Springsteen; and Native American dancers. His work resides in major collections, and in the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery. He moved to El Rito four years ago and found a 200-year-old house with a few surprises.

"My darkroom used to be a still," laughs Kennedy, tall and lean, with a slow smile. "I think it's appropriate that they mixed up hooch, and I mix up chemicals to make photographs."

Although a relative newcomer, he felt part of the community almost immediately. "The wonderful thing about El Rito is that the people here accept you and give you space. If you come here because you love this little village and respect and honor the lifestyle, people are incredibly open to you. There's a grounding, magical spirit here."

The El Rito Studio Tour, explains Kennedy, is small and intimate. "It doesn't overwhelm, and people can see an amazing cross section of very accomplished artists here. We're [otherwise] a rural farming community with no viable tourist draw." The tour, says Kennedy, changes all of that. "For two days, the town is alive with people. We become a destination, and we actually do profitable business out of our studios."

Blacksmith Michael Hennerty and his wife, artist Julie Wagner, moved to El Rito in the late 1970s. Originally from Woodstock, New York, they fell in love with El Rito and bought a big old house. "We didn't know anyone," remembers Hennerty. But he joined the church choir—he was the only non-Hispanic, and an Irish folksinger at that—and it changed everything. "It was a great experience that allowed us to get to know the community." The high point, he says, was when he sang "O Holy Night" solo one Christmas Eve.

For more than 20 years, Hennerty taught carpentry at the Northern New Mexico College campus in El Rito. When he retired, he set up a blacksmith shop, forging functionally beautiful gates, hooks, hinges, and candlesticks. He also built Wagner a studio that has been part of the El Rito tour for the past 25 years. "I create one-of-a-kind art books, and people will tell me the most fascinating stories about books, or another artist that I might enjoy," she says. "It's energizing!"

For inspiration, she needs only to step outside. "The natural world here influences my art. You walk outside and there's a bull snake on the path," she laughs.

And then there's Larry Sparks, a former Santa Fe builder/designer who bought 14 acres of land in El Rito after he retired in 1991. "It felt good when I walked onto the property; I can see for miles."

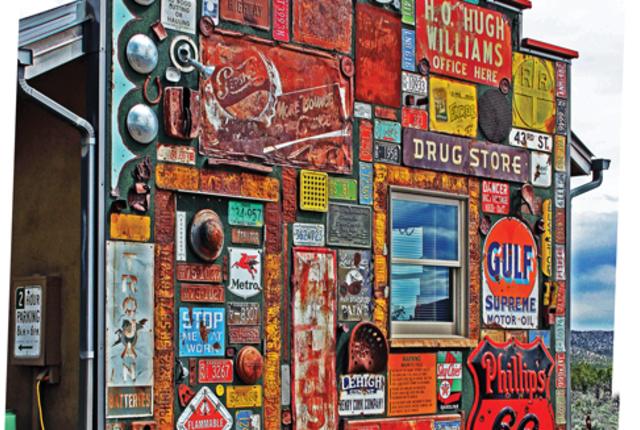

Sparks immediately started building "houses" imbued with creative whimsy. The result? A wonderfully eccentric compound of structures encased in license plates, found objects, and vintage signs. Needless to say, his outsider-art village is a hit on the Studio Tour.

Sometime after Sparks built his first small and snazzy glass-bottle-encased outhouse, he added a wonderful, light-filled studio where he sketches and paints. "People walk around with their jaws dropped," laughs Sparks, a spirited recluse who loves his solitude and the outdoors.

Cipriano Vigil moved to El Rito in 1980 to teach at Northern New Mexico College, and a few years later became the chair of the fine arts program. His passion, even as a little boy, was music. "I made guitars out of shoe boxes and cigar boxes," he remembers. "Then someone bought me a $9 guitar and I taught myself to play." Vigil got hooked on instruments, and began collecting and fashioning them and making music. He now has more than 320 in his collection and has started making cigar-box guitars again, this time with matching cigar-box amplifiers.

"I decided to do the El Rito Tour for the first time this year," says Vigil. "I think the cigar-box instruments will make wonderful gifts for grandchildren." And as an added treat, he'll invite visitors to pick out an instrument from his collection (a guitar made out of a clock, or perhaps one made from a coconut) and then will play it, and probably sing a few bars.

C. Whitney-Ward is a photojournalist and author who publishes a photographic blog, Chasing Santa Fe (chasingsantafe.blogspot.com).

Behind closed doors

For almost 40 years, northern New Mexico artists have opened their homes and studios to thousands of visitors who wend their way to their small villages and towns to meet the artists, experience the energy of their studios, and, of course, to buy wonderful art.

15th Pecos Studio Tour

September 22–23; (505) 670-7045; pecosstudiotour.com

Tucked into the east side of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, at the site of the Glorieta Pass, Pecos village, just 20 minutes from Santa Fe, is steeped in the rich history of Northern New Mexico. For centuries, ancient nomadic Indians, Spanish Conquerors, missionaries, armies, settlers, and adventurers traveled to and from the Pecos Valley. Nearby is the site of the Battle of Glorieta Pass, a Civil War struggle that ended Confederate plans to invade the West.

Duane Maktima, from Laguna Pueblo and Hopi, Parrot Clan, is a master jeweler. His vibrant work is represented in major museums, including the Smithsonian. He has shown his work at Santa Fe's Indian Market for the past 39 years, but he still finds it worthwhile to participate in the studio tour. "The Pecos tour blew me away," says Maktima, who was happily surprised by the response and the sales. (505) 757-6946; duanemaktima.com

14th High Road to Taos Studio Tour

September 22–23, 29–30; (888) 866-3643; highroadnewmexico.com

The High Road to Taos is a scenic drive that meanders from Chimayó to Peñasco, passing through traditional Spanish and Pueblo villages dating back to the 1600s and 1700s. The drive is lovely in the fall; the aspens are golden, and the sky is deep blue.

Serendipity brought plein-air painter Sally Delap-John and her husband from central California to Truchas on one of their frequent trips to northern New Mexico. They parked in front of a gallery, and on a whim, Sally walked inside and showed the owner one of her paintings. "She said that I needed to come back and paint, and I could stay with her. I took her up on her generous offer and returned again that fall and experienced the High Road Art Tour." (505) 689-2636; sallydelap-john.com

Ninth Abiquiú Studio Tour

October 6–8; (505) 685-4454; abiquiustudio tour.org

By the 1740s, the first village of 20 families, Santa de la Rosa de Abiquiú, had been established by Spaniards on the lowlands next to the Chama River. Records show that this village was built on top of an ancient Tewa Pueblo abandoned sometime in the 16th century. And four centuries later, Georgia O'Keeffe fell madly in love with the town and its environs.

For Al and Kathie Lostetter, moving to Abiquiú in the mid-'70s was a life- and art-changing experience. Their son, Owen, also an artist, has been part of the tour since he was a child. "We feel that our art grew out of our life here, inspired by the random exquisite encounters with nature. All of our prior experience of art got transformed by Abiquiú." (505) 685-4454; lostettergallery.com

Second Alameda Studio Tour

October 13–14; (505) 792-1030; alamedastudiotour.com

Alameda means a "place of trees," and is aptly named for its grove of cottonwoods along the Río Grande. This 18th-century pastoral village divides the bustling east and west sides of Albuquerque.

Alameda was originally a farming community of handcrafted adobe houses, and today you can still walk down narrow dirt roads dotted with rustic adobe homes, apple orchards, lush alfalfa fields, and vast pastureland. Alameda is home to a number of established and emerging artists, who last year formed the first Alameda Studio Tour.

Jan Swan is an abstract/impressionist oil painter who captures the grace and beauty of horses and other animals in her paintings. "Alameda is such a unique community," explains Swan, who loves to walk for miles along the canals. "It's urban, but with a definite rural feel." (505) 899-2918; zhibit.org/janswan

25th Galisteo Studio Tour

October 20–21; galisteostudiotour.com

In 1540, Coronado's expedition found a bustling, multistory Pueblo settlement of Tano Indians here, and the Galisteo basin was a thriving trade route for the Indians and, a century later, the Spanish, when they built a mission on the future town's site. Much of the tour can be done on foot.

Artist Priscilla Hoback grew up in Santa Fe. Her family owned the legendary Pink Adobe restaurant, and she had a flourishing pottery studio on Canyon Road from 1966 to 1977. In 1968, she moved to Galisteo. "I wanted to stay near family, and when I came out to look at Galisteo, I fell in love." She bought a hacienda, originally part of a sheep ranch owned by the Ortiz family. The front room is now her gallery/studio, which showcases her unique glazed sculpture. "This place inspires my work and my life," says Hoback. She participated in Galisteo's first studio tour, 25 years ago. (505) 466-2255; priscillahoback.com

31st Dixon Studio Tour

November 3–4; dixonarts.org

Tucked into the Embudo Valley, the Dixon area was inhabited by Tiwa peoples from nearby Picuris Pueblo, then settled by Spanish colonists who set up a system of acequias to provide drinking water and irrigation for their crops. Stone sculptor Mark Saxe moved to Dixon from an artist community in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Betsy Williams, who attended St. John's College in Santa Fe, worked as a trader at a Japanese bank in New York, where she became enamored of ceramics, and moved to Japan to apprentice as a ceramist. Back in the States, she settled in Rinconada, near Dixon. Williams and Saxe met, and eventually opened the Rift Gallery in Rinconada. "The tour really laid the groundwork for opening our gallery in 2005," says Williams. (505) 579-9179; saxstonecarving.com/gallery

38th La Cienega Studio Tour

November 24–25; (505) 699-6788; lacienega studiotour.com

La Cienega was a 17th-century pueblo, resettled by the Spanish in the early 18th century. Its name, which means marsh or swamp, refers to a spring that supplied water to nearby El Rancho de las Golondrinas. Nestled in a lush valley just 10 miles southwest of Santa Fe, La Cienega hosts the oldest studio tour, which traditionally opens on Thanksgiving weekend. The nearby Sunrise Springs Resort turns its atrium into a gallery, showcasing the work of artists whose studios are too small to accommodate all the visitors. The resort also welcomes art-tour visitors to stay there.

Contemporary sculptor Gilberto Romero is a fourth-generation Santa Fean. An avid bow hunter and fly fisherman, he gets his inspiration from nature. "I see shapes everywhere," explains Romero, who then sketches what he's seen and renders it in metal.

And don't miss:

Cerrillos/Madrid Studio Tour

October 6–7, 13–14; madridcerrillos studiotour.com. 27 Turquoise Trail artists welcome all comers.