From Albuquerque, drive 156 miles northeast on I-25 to exit 366 at Watrous. Proceed 8 miles on N.M. 161. You’ll find a picnic area, restrooms, and water. The visitor center has a bookstore and a small museum, and you can watch an introductory video and chat with the helpful rangers.

You’ll find food and hotels in Las Vegas (29 miles southwest) and Springer (54 miles northeast). The nearest camping areas are in Romeroville (5 miles south of Las Vegas) and Storrie Lake State Park (6 miles north of Las Vegas). The monument is open every day except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Winter hours (Labor Day–Memorial Day): 8 a.m–4 p.m. Summer hours (Memorial Day–Labor Day): 8 a.m–5 p.m. (505) 425-8025; nps.gov/foun

EVENTS

ONGOING

Glimpses of the Past March–October, experts give presentations at the Santa Fe Trail Interpretive Center. On Thursday, April 16, at 7 p.m., Visitor Services manager Debbie Pike presents “Creating a Choir of Birdsong: Restoring Native Bird-Friendly Habitats of Northeastern New Mexico.” Contact Fort Union for more programming details (505-425-8025). Third Thursday of the month, 7 p.m. 116 Bridge St., Las Vegas

JUNE 20–21

Fort Union Days Enjoy talks, living-history encampments, cannon and musket demonstrations, and guided tours.

JULY 9–10

Junior Ranger Camp For kids ages 7 to 9 (July 9) and 10 to 12 (July 10), 10 a.m.–4 p.m. Enrollment begins June 1.

AUGUST 8

Candlelight Tours Historic scenes are reenacted for visitors after nightfall. Reservations required.

The first time I visited this spot, the drill was similar: a family excursion from Santa Fe, Dad at the wheel, headed for one of New Mexico’s abundant historical sites. In this case, our destination was Fort Union National Monument.

To be honest, I don’t remember that first childhood visit to Fort Union. But my parents claim, with some legitimacy, that my younger brother and I both wound up as history majors in college because they stopped the car at every roadside historical marker in our orbit. So here’s a shout-out to Mom and Dad, and to roadside markers everywhere.

The history of Fort Union would fill a wagonload of roadside markers. From 1851 to 1891, the U.S. Army operated at this spot 30 miles northeast of Las Vegas. Here, an astonishing array of people swirled through the tragedy, glory, and everyday life that marked 19th-century New Mexico. Their ranks included Union and Confederate armies; volunteer troops from old Spanish families; African American Buffalo Soldiers; Jicarilla Apaches, Utes, Kiowas, Comanches, Navajos; women of privilege married to Army officers; women of toil who washed the soldiers’ laundry.

After 1848, when New Mexico became a U.S. territory, the military established its presence at this strategic locale, which contributed two necessities: access to a transportation route (the Santa Fe Trail) and to watering holes, which travelers called Los Pozos. The first fort lasted 10 years; it left little trace, partly due to its shoddy construction. The second, built during the Civil War and lasting only two years, featured a star-shaped earthwork and, again, buildings that left something to be desired. Visitors today see the extensive remnants of the third and more elaborate fort, which the Union forces set to building in 1863, after driving the Confederates from the territory. From there, the quartermaster depot supplied other southwestern military posts with goods that arrived via the Santa Fe Trail. In 1891, with military campaigns at an end, and with the railroad claiming superiority over the trail, the Army abandoned the fort. It became a national monument in 1954.

I do remember my second visit to Fort Union. It came when I was a ninth grader, on a school-sponsored winter camping trip around northern New Mexico, sharing a pup tent with my friend Linda. I delighted in its silence and mystery, with the wind sighing through the tall grass, the lone chimneys of the officers’ quarters glowing in the sun. I felt a quiet, powerful thrill as I gazed at the Santa Fe Trail, its wide swales pressed into the earth by 60 years of wagons and hooves. The atmosphere whetted my keen appetite for history, for the people who made it, and for the places where it happened. Fort Union became another signpost guiding me to study the past. What a gift.

Two decades later, I was living in Tucson, Arizona, putting that history degree to use. I edited publications at the Arizona Historical Society by day and studied for a master’s degree by night. I often came across mentions of Fort Union in the course of my work and studies, and got a kick out of it every time. Reading accounts by 19th-century officers’ wives who had lived at the fort, I’d think, Hey, I’ve been there. I also added to my library the classic Land of Enchantment: Memoirs of Marian Russell Along the Santa Fe Trail. During her five round-trips on the trail (the first at age seven), Russell logged sev- eral stays at Fort Union and recalled it in loving detail. At a museum shop in Santa Fe, I bought an audio version of Russell’s account, titled I Remember the Old, Old Trail, because its musical arrangements were the creation of John Eddy, a family friend from Santa Fe. How about that— Fort Union still held surprises for me.

During those Tucson years, I found a new friend in Nick Bleser, a retired National Park Service ranger. Another gift: He had started his NPS career at Fort Union in 1963. His vivid stories of the place—hiking the hills, befriending cowboys, discovering arrowheads—inspired me to return for a long-overdue visit.

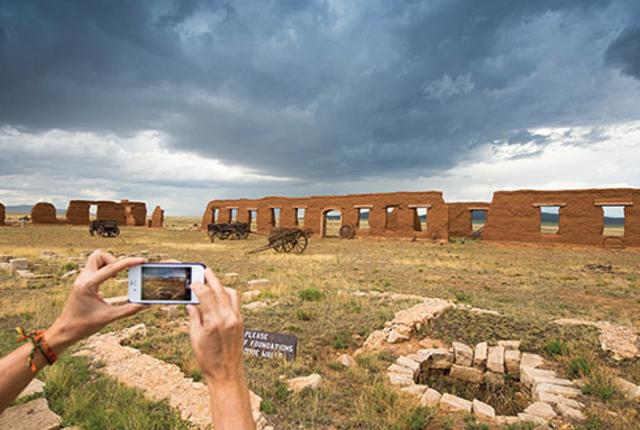

Fort Union’s adobe remnants.

So I made a third sojourn to Fort Union, on a summer day in the early nineties, this time with a friend from grad-school days at the University of Arizona. With that deep pleasure known to history majors (or history nerds, some might say, and that is okay with us), we poked around the quartermaster’s corrals and pondered those trail ruts. The surprise this time: the bull snake that crossed our path. I’m telling you, Fort Union knows how to keep a gal on her toes!

As I planned the trip to research this story, I wondered what the place would have up its sleeve. It had been a long time. You know the feeling—when it’s been too damn long since you spent time with an old friend. Can you pick up where you left off?

For Fort Union and me, the answer came in the form of an astounding treasure from a friend and her father: the unpublished account of an Army wife who lived at Fort Union in 1870. She happened to be the great-great-grandmother of a friend. Ellen Stover Dickson Wilson, a 21-year-old New Jersey native, traveled to New Mexico with her husband, Lieutenant Colonel William Potter Wilson; their African American servant, Rachel; and their two-month-old son, Alan. After a bone-crunching, 300-mile stagecoach ride from the Colorado towns of Kit Carson and Colorado Springs, followed by a week’s stay in a primitive one-room cabin in Cimarrón, New Mexico, the Wilsons arrived at Fort Union. “I shall never forget the blessed sight of that big regular parade ground . . . with the flag flying and the band playing and, most beautiful of all, such a welcome from perfect strangers,” wrote Ellen Wilson many years later, with a relief that leaps off the page.

My journey with my father was a lot easier than the Wilsons’—a smooth 90 minutes from Santa Fe. The monument offered up a fine welcome as we drove through the Fort Union Ranch, between the highway exit and the visitor center: two cowboys on horseback driving a herd of Black Angus cattle. We trekked the longer of the two paths that edge that “big regular parade ground.” I gazed with fondness at the trail ruts and thought about Ellen Wilson and Marian Sloan Russell, who once paced the flagstones. And that silence of the plains that my memory had cherished? Well, we learned from ranger Suzan Schaaf that Fort Union had, of course, been far from quiet. Army officers had barked orders in the barracks, mules had brayed in the corrals, and freight wagons had rumbled down the Santa Fe Trail.

Our fellow tourists at the monument included a mama bear and her two cubs; the vigilant staff had alerted visitors and kept a careful eye on the shaggy trio. As we motored away, Fort Union gave us one more quiet thrill—one of the cubs rambling across the road.

Fort Union, it was great to see you again. Thanks for everything.