A CHRISTMAS STORY

The way James Mullings tells it, a bunch of plywood cutouts gave the town of Ratón its Christmas spirit. Now 89, Mullings remembers how, in 1957, he moved to Ratón and took a job teaching at the junior high. He had missed the early years, when his fellow members of the Lions Club trudged up the hills of Climax Canyon Park lugging giant painted wooden angels and shepherds to build a re-creation of the City of Bethlehem. The pilgrimage soon became a tradition and, today, a don’t-miss sign of the season.

The town had some tough years after World War II, and the story of Jesus’ birth reminded folks that there is light and hope even when events test your mettle. The principal of Mullings’ school dreamed it up, he says. Inspired by a display in the old mining town of Madrid, he persuaded the Lions to set up a Nativity scene on the courthouse lawn. People loved it. So they decided to move it and expand it. The little crèche became 18 lighted and narrated scenes spread along the road that winds through the canyon. The power company donated electricity.

Police officers volunteered to turn the lights off after the last of the visitors had walked or driven down the hill. Enthusiasm spread to residents who lived along the roads leading to the display. Families competed for a best-decorated-house prize. They nicknamed a stretch of the road Toyland and populated it with pinewood characters from children’s stories. At first it was Mother Goose and Snow White, but over the years Big Bird, E.T., and SpongeBob SquarePants joined them. (They’ve been so popular that some disappeared under cover of darkness—E.T. went missing almost immediately.)

The Lions start working on the display in September and hope to have it ready by Thanksgiving, but it gets a little harder each year. “Some of those scenes are unwieldly, and especially if you run into snow, you have problems of negotiating a hillside with a cumbersome piece of plywood,” Mullings says. But the community has pitched in and, for the past few years, a motorcycle club and the high school football team have helped. It happens, one way or another. And like the magi and the shepherds, Ratónites make their way up the hill to see the scenes and hear the story. “The thought has been in our minds once or twice to fold it up and not do it,” Mullings says, “but then the tradition of doing it and the thought of keeping it going prevails.” —GD

More Information: (575) 445-3689

ONE-TRACK MINDS

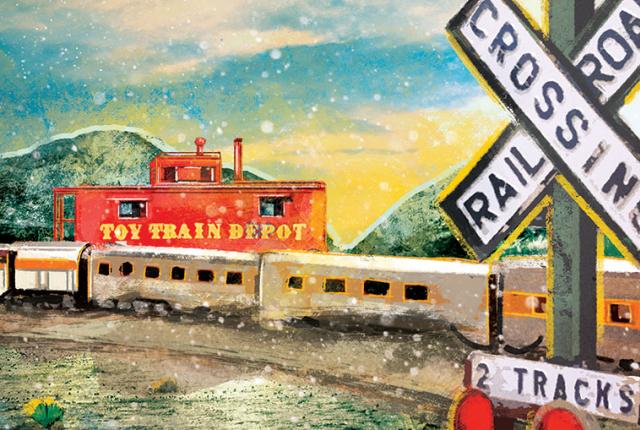

Four miniature locomotives chug around the two-mile track at Alameda Park in downtown Alamogordo. Three of them, originally built in the 1950s as amusement rides, sport classic midcentury designs—mimicking the Baltimore and Ohio, Union Pacific, and Western Pacific lines—and, thanks to meticulous upkeep, remain in nearly perfect vintage condition. The fourth train, though, is different. The 1865 was created specifically to capitalize on America’s postwar fascination with all things Western. It’s modeled after a real B&O steam train, with a tall black smokestack, a green coal tender, and a shiny red cowcatcher at its nose. Chuffing along on rails just 16 inches apart, its two 12-seat cars are no taller than a yardstick—and neither are many of the passengers who will board it for the once-a-year Alamo Holiday Express.

“The kids always want to ring the bell; dads always want me to open it up so they can see the motor,” says Toy Train Museum manager Joseph Tuttle. It’s worth seeing under the hood. The air-cooled, solid-block, four-cylinder Wisconsin motor was the workhorse of its day. Designed for heavy-duty, high-torque applications like hay balers and other farm equipment, Wisconsins were ideal for pulling three-ton trains. “It’s a real basic direct-injection carburetor motor,” Tuttle says. “It’ll do whatever you tell it to do."

On December 16, Tuttle will drape it in twinkle lights and tell it to shuttle dozens of kids around the park and return them to the depot, where they can whisper their Christmas wish to Santa. (Spoiler alert: It’s probably a train set.) These tiny engines have departed regularly from the Toy Train Depot for nearly 30 years, but they’re relatively new to the 100-year-old station house, which served the Frijoles Line, in the onetime town of Torrance, near Vaughn, before being moved by mule train to Corona and eventually trucked to Alamogordo. On Holiday Express day, the depot stays open late for hot chocolate, cookies, and some ogling of exhibits, including a 1,000-square-foot HO-scale model of 1940s-era Alamogordo.

Last year, Tuttle didn’t really advertise the event, but turnout was still good. This year, he hopes for repeat customers. And if you just can’t make it to Alamogordo, other train options await. Young (and older) train buffs love the authentic steam power of the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad’s Christmas Train, the glowing magic of the Albuquerque BioPark’s Polar Bear Express, and the festive atmosphere of the Rail Runner’s journey to Santa’s Village at the Santa Fe Railyard. —GD

More Information: Toy Train Depot, (575) 437-2855, nmmag.us/AlamoExpress. Cumbres & Toltec, (575) 741-3126, cumbrestoltec.com. BioPark, (505) 764-6200, riveroflights.org/polar-bear-express. Rail Runner, (866) 795-7245; riometro.org

FELIZ HANUKKAH

Green chile latkes? Jewish buñuelos? A dreidel with Spanish roots? Welcome to Hanukkah in New Mexico, an ancient holiday steeped in our state’s unique cultural blend. It's a lot of steeping, when you consider that the earliest Jewish DNA came to New Mexico with Spanish conquistadors and that the territory’s first synagogue was built in 1884 in Las Vegas.

Then, as now, Hanukkah was a minor Jewish holiday, but still an important one. The Festival of Light commemorates the liberation of Jerusalem’s Temple in 164 BC, where the victors found only a day’s worth of oil to keep the holy space lit. Miraculously, it lasted for eight days, and so today, each night of Hanukkah, we light a candle on the eight-branched menorah.

Hanukkah also means eating foods cooked in oil, like latkes (potato pancakes) and the fried pastries known as sufganiyot and burmuelos. As world wanderers, Jews always put their spin on local foods. When in New Mexico, we serve latkes as New Mexicans would—with green chile or red chile sauce, along with the classic applesauce and sour cream. And if the word burmuelos sounds similar to the Spanish buñuelos, you’re right. Both originated with Spain’s Sephardic Jews. But burmuelos are usually filled with jelly.

Spinning the top-like dreidel for gelt (chocolate coins) also boasts a New Mexico twist: a similar top game, called topo or trompito, that’s unique to northern New Mexico. “Some think it came here from Mexico, then got assimilated into the German version of the game when Jews arrived in the mid-1800s,” says retired anthropologist Ron D. Hart.

Until recent years, Hanukkah celebrations were family-focused. Today, perhaps because of the interest in the legacy of New Mexico’s crypto-Jews, the desire to raise general awareness of Judaism, and Hanukkah’s arrival in an already festive season, Jewish communities welcome everyone to the party. Because, well, everybody loves a party. Especially an eight-day party (December 13–20 this year).

The Alevy Chabad Jewish Center, in Las Cruces, erects a 12-foot metal menorah in Old Mesilla Plaza on the Sunday of Hanukkah and invites the community to the lighting ceremony, along with games, arts and crafts, food, and a free concert. On the Santa Fe Plaza, you can watch participants light an artist-crafted eight-foot menorah made from rebar and other industrial materials, while enjoying latkes, doughnuts, hot chocolate, and live entertainment. But Albuquerque—oh! The Hanukkah Night Glow, now in its second year, creates what sponsors bill as the world’s largest menorah, using hot-air balloons, luminous against the darkening sky. I nudged, but the organizers were still firming up details. All I can say is: These balloons I gotta see. —KK

More Information: Las Cruces, chabadlc.org. Santa Fe, santafejcc.com. Albuquerque, (866) 795-7245, menorahglow.com

DO YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR?

In Mesilla, family, history, and tradition matter—especially at Christmas, when people gather to make tamales and attend Midnight Mass. One of the best rituals, though, harks back to a Victorian ritual of joining others to lift your voice in song. Luminarias line the Mesilla Plaza’s sidewalks. Twinkle lights drip from the gazebo. Church bells ring. And the voices sing out, bold, bright, and clear. Every year (no one remembers how many years), hundreds of people have converged around dusk on Christmas Eve to see the luminarias and sing the carols. Everyone who wants to sing gets a songbook, a candle, and a cup of Mexican hot chocolate from Andele Restaurant.

It’s pretty spectacular, says Orlando-Antonio Jimenez, a professional soloist and devout Catholic, who will lead the crowd for the second year in a row. “It’s like: How come you sing here but you don’t sing in church?” he says, chuckling about the singers who participate. “On the Plaza, for some reason, the spirit of Christmas takes over.”

Aside from people snapping pics with their smartphones, it can feel like a trip back in time. Singing familiar songs out loud—instead of hearing them piped through speakers in a store—just seems more meaningful, eternal, powerful. The caroling reminds Jimenez of times, some not too long ago, when people didn’t have anything to give other than a song. For him, to stand in the gazebo and sing to his neighbors is a heartfelt gift.

This year, he plans to sing “Vamos Todos a Belén” (Let’s All Go to Bethlehem). For this third-generation New Mexican living in a border town, it’s melodic and poignant. “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph weren’t Mexican,” Jimenez says, “but they were this poor family, this refugee family, and when I compare their journeys, I get very emotional.” —GD

More Information: (575) 524-3262, nmmag.us/MesillaCaroling

THE SECOND-BEST ELECTRIC AMPLIFIES JINGLE BELL FLOAT

Twinkle Light Parades abound in so many small towns across the state that you might think they’ve cornered the market on the event. They haven’t. Albuquerque’s electrified romp has grown into kind of a big-city big deal. People get themselves and their rides all dolled up to strut through Nob Hill, waving at thousands of people lining Central Avenue. On December 2, you’ll see a mile-long line of fringe-limned cowboys on horses, springing acrobats, sequined dancers, marching bands, and Girl Scout troops. Some of us sign up year after year to drape wildly colored lights all over hot rods, lowriders, pickups, and trailers, many bearing incredibly elaborate and meticulously planned designs. Not our float.

Actually, to call it a “float” is pretty generous. What my friends and I have is a giant, weird-looking old European fire truck painted Day-Glo orange, and its six-foot-tall trailer, both of which look like we threw a dozen fully decorated Christmas trees into a chipper and aimed it at them. Last year we lashed an inflatable, illuminated R2-D2 to the roof, just because we had one. My friend James Opel, a Bernalillo County firefighter, has other unusual trucks in his collection, but this one is our parade vehicle of choice.

Here’s the routine that my motley group of friends and our kids have followed every year since 2011: A few days before the parade, we slather the truck with all the lights, battery-powered candy canes, and plastic snowflakes we can scrounge up. Then, the night of the parade, we pile on as many people as we can fit. We wear leopard-print Santa hats and flashing reindeer antlers. We play funny songs. We jive, jitterbug, gyrate, and head-bang down the road to the holiday stylings of El Vez, the Ramones, James Brown, Loretta Lynn, and a little Snoop Dogg.

People lining the route occasionally fail to grasp our theme. That’s probably because we don’t have one. We call our float the “Jingle Bell Party Truck,” and that’s about it. We have a party on a truck. With bells.

What we lack in planning, vision, and skill we make up for with an abundance of holiday spirit and the eggnog-fueled energy to booty-shake for two hours straight. At least that’s what the celebrity judges must have thought when they awarded us second prize last year. Turns out they evaluate the floats not on electric perfection but on creativity, holiday spirit, and “wow” factor. The fact that they gave first place to the Albuquerque Metropolitan Area Flood Control Authority’s float and its Tumbleweed Snowman—an inanimate object—made our hearts smolder like lumps of burning coal. This year, we will take you down, Snowman. Same place, same time. —GD

More Information: (505) 768-3556, nmmag.us/TwinkleLight17

THE NUMBERS GAME

Luminarias flickering from the rooftops, sidewalks, and parking lots during San Juan College’s annual display in Farmington: 40,000.

Dump trucks of sand, each with an eight-ton load, needed to fill those 40,000 paper bags: 2.

Kids (mostly kindergartners) recruited from Farmington’s 10 elementary schools to help fill those bags with just enough sand to cradle a candle and keep them from blowing over: 700.

Full days it takes to fill the bags: 2.

Amount of sand that goes into a kindergartner’s hair, shoes, and mouth: Incalculable. Community volunteers who bend over and light every candle in every bag, all over the whole dang campus, as if their backs are still as young as an elf’s: 500.

Hours it takes those 500 volunteers to light every wick without burning too many fingers: 1.5.

Free cups of hot chocolate doled out to warm up big hands and little fingers as people wander through the maze: 3,000.

Walkers who brave all kinds of weather (sometimes all kinds of weather in the same night) to see the lights up close: 8,000.

Drivers who keep the heat blasting and their foot on the brake as they snake through the campus: 9,000.

Dial numbers of KSJE, the community college’s FM radio station, which broadcasts carols over loudspeakers (whether you like Andy Williams or not): 90.9.

Classes held the night of the display: 0.

Telescopes set up in the courtyard of the planetarium for that night's annual Star Gaze: 1.

Years that financial-aid director Mindi-Kim Schrum has helped out with the luminaria display: 21. Years that San Juan College has been putting on a luminaria display: 39.

Years we hope they continue: ∞.

Date of this year’s event: December 2. —GD

More Information: nmmag.us/OMGsomanylights