AT A TEMPERATURE OF 1,000 DEGREES—the heat of lava—the glass at the end of the blowpipe resembles a fiery sun at dusk as it leaves the furnace for the workbench, cooling enough on the way to reveal the reds and purples in its composition. Like molten taffy, it twirls against a wet newspaper, taking the barely beginning shape of a vessel. From furnace to bench it dances, back and forth, until the moment when it will fill with the artist’s breath, expand like a crystal lung, and morph into its final form. From here it will go into a kiln, where the piece will anneal overnight before entering the realm of human stories for the next one million years.

In the world of Indigenous glass artists, Isleta Pueblo’s Tony Jojola is an OG—original glassmaker. Forty-six years ago, this son of Native potters was the first Pueblo artist in New Mexico to take up glass. As he mastered his molten art, other Indigenous artists found their way to the medium. From May 1, 2021, through June 30, 2022, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, in Santa Fe, will display Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass, an exhibition accompanied by a Museum of New Mexico Press book by guest curator Letitia Chambers.

Together, they herald a coming of age for Native glassmakers who use the elements of sand and fire to reimagine traditional basketry, pottery, weavings, and fetishes into luminous masterworks. It’s no coincidence that many of them share an association with the Institute of American Indian Arts and with famed glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Founded in 1962 as a high school on what is now the Santa Fe Indian School campus, IAIA became a two-year college in 1975, offering associate’s degrees in studio arts, creative writing, and museum studies. During that flagship year, Jojola enrolled and began studying under Osage sculptor and glass artist Carl Ponca. He had inherited the program from Chihuly, who had set up a kiln and glass hot shop in an old barn on campus in 1974, while he was on loan from the Rhode Island School of Design.

In the 1960s and ’70s, many Native artists pulled away from preservationist and traditional work to explore contemporary art, soon making a space for themselves in the larger world of fine art for the very first time. (During that period, the Pilchuck Glass School, north of Seattle, attracted Native artists from the Northwest region.)

Robert “Spooner” Marcus teaches weekly glassblowing classes at Prairie Dog Glass, in Santa Fe.

“That was such an incredible period of creativity at IAIA, and the artists who came out of the period have really led the contemporary Native American art movement,” says Chambers. “The fact that glass was offered, even for those artists who didn’t decide to become glass artists, showed them that artists had their choice of media. They didn’t have to stick with the traditional if they didn’t want to.”

Chambers, who is of Cherokee descent, has worked on Native American issues for most of her career, including 10 years on IAIA’s board of trustees and as chief executive officer of the Heard Museum, in Phoenix, from 2009 to 2012. The book idea came about last year, because she felt the time had come to tell the stories of glass art in Indian Country and the work of IAIA’s founder, Cherokee artist Lloyd Kiva New. The book features 33 artists, whose works are also in the exhibition. With a total of 140 pieces of glass by North American Indigenous artists, plus two Maori and two Aboriginal Australian artists, this is the largest exhibit of its kind, Chambers says.

“What I find so interesting is that the artists have chosen to embody the intellectual content of their Native cultures in the glass,” she says. “They are interpreting traditional stories and designs and expressing cultural ways of knowing in a medium that was not traditional.”

Tony Jojola presents one of his masterworks at Isleta Pueblo.

To hear Jojola tell it, glass was an inevitability, not just for him but for other Native artists. Coming from a family of potters, he began experimenting with heat and the varied results it produces with different clays long before he enrolled at the school. When he discovered glass, he says, it was like seeing another form of clay, albeit one you can’t touch while forming the pieces.

“Glass was bound to take off,” he says. “Even Lloyd Kiva New knew that. He explained to us that jewelry wasn’t Native, but when silver was presented to us in the way that it was, the Natives took off and ran with it. That’s exactly what happened with glass.”

Read More: At Jemez Pueblo, mother-and-daughter potters share generations of knowledge with others.

Glass needs roughly a million years to break down and decompose, whereas pottery takes closer to 10,000. This gives Indigenous artists a medium to honor and share their cultures in a way that will last a very long time, Jojola says. His pieces reflect his Tiwa culture in designs such as his bear fetishes, as well as vibrant pots and vessels.

“Our cultures are so rich, and we have so many tribes left that can interpret it in glass,” he says, adding that this is a reason he’s dedicated much of his career to teaching young people how to work with glass.

Tewa artist Robert “Spooner” Marcus (Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo) is one of Jojola’s protégés from the Taos Glass Arts and Education program, which he co-founded and operated during the 1990s. “I remember walking into my first hot shop and feeling like I was home,” Marcus says, adding that glass helps keep him in the moment, which is what makes it a great tool for helping kids develop healthy coping skills.

Robert “Spooner” Marcus works on a new creation at Prairie Dog Glass, in Santa Fe.

Robert “Spooner” Marcus works on a new creation at Prairie Dog Glass, in Santa Fe.

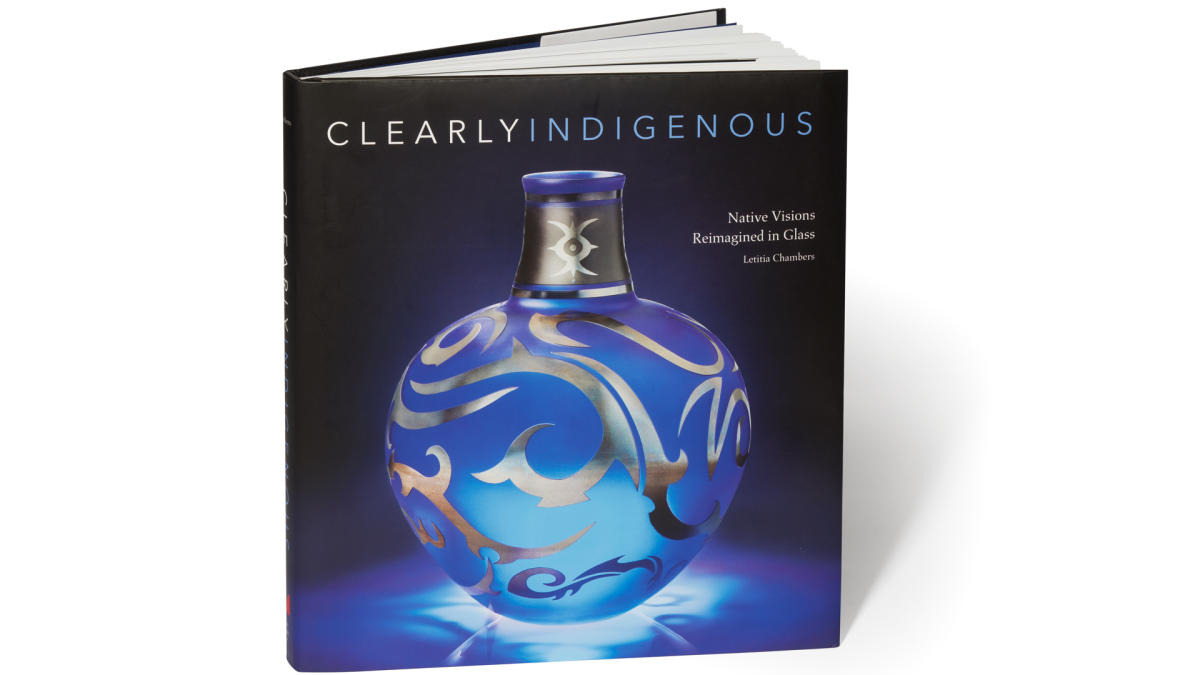

Cobalt Cosmic Blue, his blown and sand-carved pot featured on the cover of the Clearly Indigenous book, was created in 2010, when he began experimenting with new forms of expression through glass in what he calls “deeply personal ways.”

“I wanted to tattoo the glass,” he says of the cover piece, which took him months to create using stencils he designed on a computer program for tattoo artists. Glass, he says, as well as computer programs, are contemporary mediums that he melds with his experiences of being Tewa and growing up in Española.

Marcus stumbled into the field in the early 1990s, when his mother sent him to apply as a glassblower’s assistant to keep him out of trouble. It wasn’t until he began taking mentorships with Jojola and other Native artists that he realized the potential glass has to communicate culture and story.

“It’s mysterious,” he says. “You never stop experimenting with it.”

Today he works and teaches out of Prairie Dog Glass, in Santa Fe, where he focuses on vessels that combine colored glass and etched patterns to achieve the vibrancy of an abstract painting. Marcus offers pieces in a range of sizes and prices, in addition to classes and workshops, which he hopes will make glass art accessible to everyone. He’s most inspired by the collaborations he sees among Indigenous glass artists to create pieces that combine cultures, techniques, and stories.

Santa Clara Pueblo artist Tammy Garcia and Tlingit artist Preston Singletary, for example, collaborated to interpret traditional Santa Clara pottery concepts with glass. Singletary and his team blew the glass; Garcia sand-carved the designs. “I had scaled the shapes on graph paper,” says Garcia, a noted contemporary potter. “The designs inspired the colors I chose. Each color was intentional. This transition from clay to glass gave me very different options, because glass could be transparent or opaque. How light goes through this material is special—designs will appear to overlap.”

Diné artist Carol Lujan cuts and fuses colored glass in a kiln to reimagine elements from Navajo life, culture, and the environment. She’s won admirers for her glass rugs patterned after Navajo weavings. Lujan, who moved into the arts after a successful career in academia, says that her life’s work has always been to express the best qualities of Indigenous cultures.

“It’s interesting to blend traditional Indigenous designs using a nontraditional art form such as glass,” she says. “I hope to achieve beauty and balance in my work, and to capture the strength, beauty, humor, and sovereignty of the Native cultures of the Southwest.”

GLASSIFIED ART

See Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture through June 2022. Check the museum’s website for possible changes in operating hours, exhibition dates, and potential artist talks and events.

710 Camino Lejo, Santa Fe; 505-476-1269