Hopi Dancers (State I), 1974, by Fritz Scholder. Courtesy of Tamarind Institute.

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST, printmaker June Wayne devised a bold plan to rescue the dying medium of lithography. It was 1959 when the artist, entrepreneur, and educator realized she could count on one hand the remaining artisan printers in America who “pulled stones,” using a press to faithfully transfer an image drawn by an artist on a limestone tablet to paper.

Wayne said “the foreseeable end to the kiss of an inked stone on a sheet of velvet-white paper” simply would not do. She asked the Ford Foundation for a grant to establish a lithography workshop. Goal number one? To create a pool of master printers in the United States who would work intimately with artists to produce vibrant, nuanced prints of their work in any medium: paint, pastel, drawing, photography, and even sculpture.

More than 60 years later, the nonprofit workshop Wayne created in Los Angeles—now the Tamarind Institute at the University of New Mexico—is a stronghold of lithographic training and a thriving monument to artistic collaboration. Housed on the UNM campus, the institute boasts a state-of-the-art print shop and public gallery with an inventory of 8,000 Tamarind-produced lithographs. It hosts around eight students a year who train in traditional lithographic printing techniques, in close collaboration with a steady lineup of visiting artists, and awards a special master printer designation to chosen students who make it through an intensive second year.

Throughout its tenure as keeper of the litho flame, Tamarind has collaborated with a star-studded lineup that has included Ed Ruscha, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Louise Nevelson, Judy Chicago, Kiki Smith, Harmony Hammond, and Fritz Scholder. It gave birth to multiple generations of printers who now lead more than 80 workshops or printmaking programs worldwide. Around 100 collectors eagerly snap up Tamarind’s exclusive annual Collectors Club editions, made with visiting artists. Other prints within its vast archive are for sale on the institute’s website.

Students Brian Wagner and Lindsey Sigmon are at work in the print shop.

Students Brian Wagner and Lindsey Sigmon are at work in the print shop.

New Mexico has played a key role in the development and sustainability of the Tamarind Institute. Originally named after the street in Hollywood where it was established in 1960, the workshop settled into Albuquerque a decade later, after its associate director, Clinton Adams, and technical director, Garo Antreasian, joined the faculty of UNM’s College of Fine Arts. When Wayne resigned, it made sense for Adams to take over and to fold the institute into the university.

Tamarind’s current director, Diana Gaston, says the Land of Enchantment holds a special sway over artists who come to the institute to make editions. “Visiting artists completely fall in love with New Mexico,” she says. “They also recognize what a rare place this is, to have a quiet, uninterrupted place to work.”

Read More: Nine Native women tell their stories through printmaking at the UNM Art Museum.

In 1970, Tamarind invited Fritz Scholder, a painter then living in Santa Fe, to collaborate on the first major suite of lithographs in its new digs. The result was a numbered edition of 75 called Indians Forever. The first in a series of Scholder-Tamarind collaborations over the next decade or so, it challenged stereotypical depictions of Native Americans with signature Scholder wit.

The bold, flat color planes of Scholder’s early Tamarind lithographs “set a tone for the kind of prints we make,” Gaston says. “One of lithography’s great attributes is that it can look like anything—a screen print, a charcoal drawing, a watercolor. It can take on whatever the artist wants it to do.”

No matter the medium, the learning curve is steep for artists who come as residents to the ultra-creative, extra-collaborative workshop model for which Tamarind holds worldwide fame. Inspiration and a new way to reinvent print can arrive out of the clear blue New Mexico sky. That was the case for paper artist Matthew Shlian, whose 3-D, six-color lithographic monoprint collage Every Line Is a Circle If You Make It Long Enough (2017) dominates the bottom floor of Tamarind’s Central Avenue gallery.

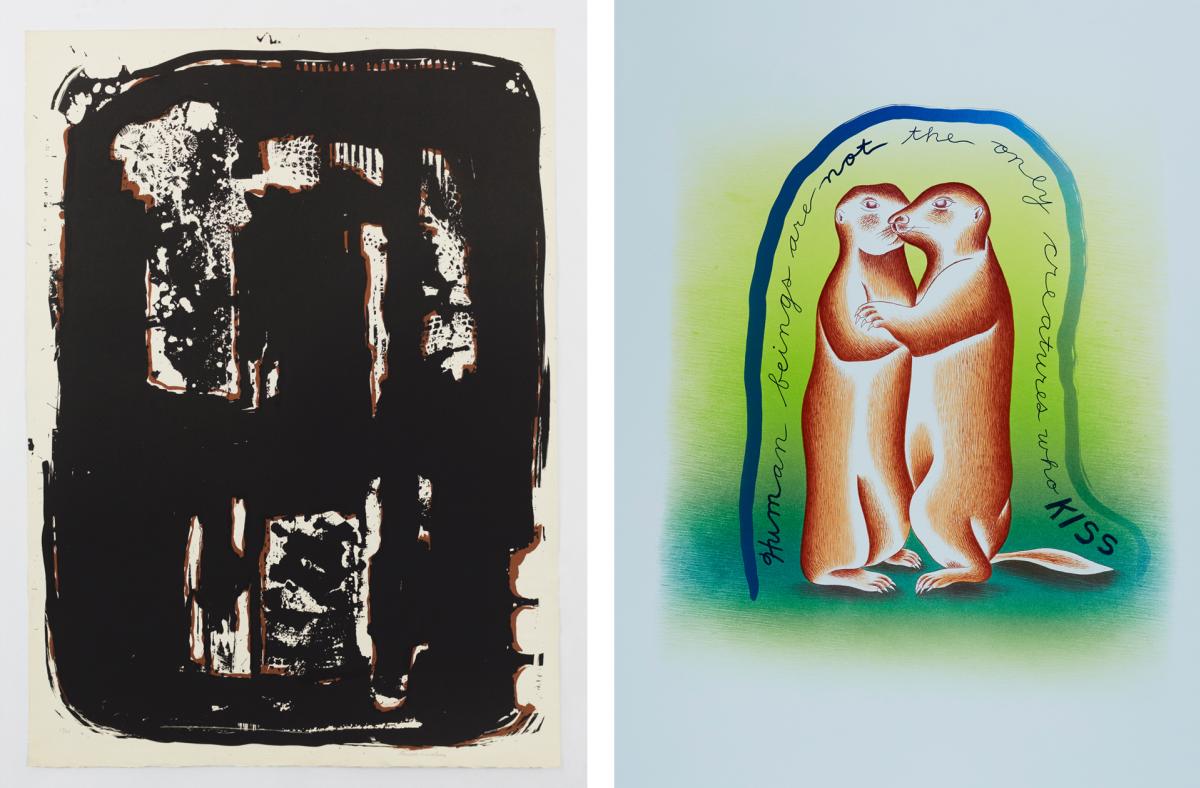

Untitled, 1963, by Louise Nevelson (left) and In Praise of Prairie Dogs, 2019, by Judy Chicago (right). Courtesy of Tamarind Institute.

Untitled, 1963, by Louise Nevelson (left) and In Praise of Prairie Dogs, 2019, by Judy Chicago (right). Courtesy of Tamarind Institute.

Master printer and workshop manager Valpuri Remling remembers a moment that proved instrumental in the creation of the undulating indigos and baby blues that color Shlian’s monumental folded-paper installation. It happened on a fateful drive down the Turquoise Trail as the two headed back to Albuquerque from a day in Madrid.

“He was looking at the sky, going, ‘Oh my gosh, imagine if we could have paper that color,’ ” she recalls. “I said, ‘We can do that!’ ”

Her attitude typifies Tamarind’s collaborative method. That kind of interpretive skill also plays into the training of student printers. “It’s about listening between what the artist says and being able to translate that to lithography,” she says. “It’s our job to present them with the answers.”

The ultimate answer, the press itself, also boasts an Albuquerque tie. In the 1970s, mechanical engineer and Takach Press Corporation founder David Takach Sr. designed a new, more efficient press for the workshop after being asked to troubleshoot its machines. From people to tools, that care and oversight has won the institute kudos.

Master printer and workshop manager Valpuri Remling poses in Tamarind's print shop.

Master printer and workshop manager Valpuri Remling poses in Tamarind's print shop.

Santa Clara Pueblo artist Rose B. Simpson, who works in ceramic, metal, painting, and performance, calls Remling and 2020–21 Frederick Hammersley Apprentice Printer Alyssa Ebinger “the magical paper people.” In an artist talk for her 2021 Tamarind residency, Simpson described the conception of her printmaking process. Guided by the printers’ unorthodox thinking, she made experimental forays into sewing and crushing paper together, listening to its sound.

“Printmaking has this really vital string between sculpture and the paper,” Simpson explained. “There are so many layers that are so visceral and yummy in a very sculptural sense—and yet, it’s turning into paper. I’ve been thinking about how we pull that visceral engagement of sculpture into a flat world.”

Santa Fe santero Luis Tapia twice joined with Tamarind to translate his sculptures into prints. “I had to try to reorganize my head,” he says of those residencies. His four-color 1998 lithograph En Honor de Frida Kahlo pays tribute to the Mexican artist with a burnt-orange sacred heart amid a whimsical purple wash. He describes the Tamarind collaboration as instrumental in building both his painting and sculpting techniques.

“I understood dimension more,” he says. “I could see where curvature had to be, and I took that and put it into my sculpting.”

Director Diana Gaston oversees the development of the Tamarind Institute.

Director Diana Gaston oversees the development of the Tamarind Institute.

In the workshop on a sunny April morning, an air of solemn concentration prevails. First-year apprentice printer Austin Armstrong carefully rolls thin layers of greasy oil-based ink onto a surface, counting the number of passes that will give him the soft wash of pastel color he needs. Beside him, education director and master printer Brandon Gunn sponges a plate while explaining the essential idea behind lithography: Oil and water don’t mix. Their reaction ensures that the printing plane (be it heavy limestone or an aluminum plate) repels ink everywhere except on the image itself.

Armstrong explains the story behind the print he is making, by artist Eric J. Garcia. It depicts Garcia’s late cousin José, who got around in a wheelchair, against a topographical New Mexico backdrop that honors José’s commitment to acequia culture, community activism, and the traditions of the Penitente Brotherhood. “He’s originally from Albuquerque,” Armstrong says of the artist. “We shared a lot of discussions about community, culture, and, really, his heart.”

For a practice built on the repellent tension between two liquids, the printmaking at the Tamarind Institute also represents a certain kind of harmony—the creative alliance between artist and artisan, and the infinite possibilities in between.

The Tamarind Institute’s world-class lithographic prints rely on teamwork, precision, a variety of tools, a fair amount of physical exertion, and a sense of humor.

The Tamarind Institute’s world-class lithographic prints rely on teamwork, precision, a variety of tools, a fair amount of physical exertion, and a sense of humor.

FINE PRINT

Get up close and personal. Schedule a gallery visit to the Tamarind Institute on the UNM campus. Two floors showcase a rotating exhibition of prints created with visiting artists; new releases are shown through August. 2500 Central Ave. SE, Albuquerque; 505-277-3901

Tune in to an artist talk. Painter Hung Liu discusses her collaborations with the workshop in a virtual program August 21 at 4 p.m.

Join the club. Tamarind’s annual Collectors Club editions are available to 100 art lovers who sign up to receive a print from a surprise guest artist. For the 2021 Collectors Club, the annual membership ($700) offers a choice of prints from six groupings that span six decades of artistic collaboration—and includes a discount on a future purchase.