Toadlena, (translates to “Bubbling Water” in Navajo) Trading Post, a designated National Historic Site, nestles in the forested foothills of the Chuska Mountains at the end of a sparse road, 75 miles north of Gallup where the Navajo Nation reaches into the western edge of New Mexico. Since 1909, the trading post has operated in the traditional style—swapping hand-crafted weavings and jewelry for sundry goods from shelves lined with Bluebird flour and cans of Spam and Hunt’s tomato sauce. Mark Winter has been at the helm since 1997, when he negotiated and acquired the lease from the Navajo Nation.

Winter has spent a career selling and studying Navajo weavings, in particular the Two Grey Hills style. He’s spent the last 25 years helping to keep the style alive from this remote outpost. “When I started collecting Two Grey Hills weavings, the weavers were anonymous,” he says. “I’d have a 50-year-old masterpiece on my hands and not know a thing about the person who made it. These things were so good—and so unknown.”

He’s since traced the genealogy of the region’s artists in his book The Master Weavers and supported about 100 weavers with supplies and a place to sell and market their creations. He’s sold about 8,000 rugs and blankets and poured $5.5 million in the area’s artists. “I fell in love with all these grandmothers who were weaving, and it basically ruined my life,” he jokes. “We’ve marketed rugs to the point that weaving has carried into another generation, and we hope it keeps up past that.”

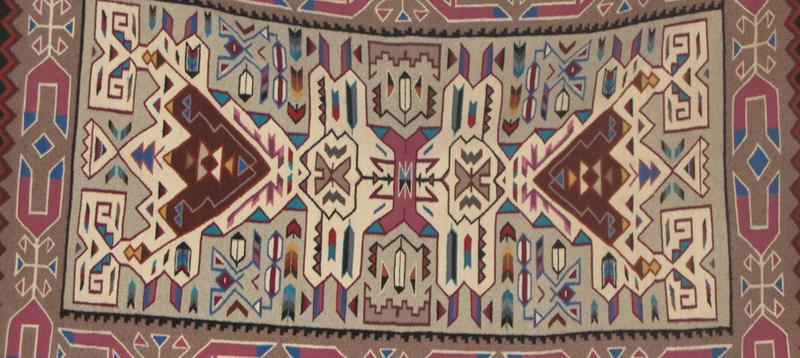

Many of the weavers still touch every part of the weaving process. They raise and herd churro sheep, prized for the texture of their wool, shear the sheep, spin the wool, and weave it into intricately designed blankets that exemplify the earthy hues of the sheep’s wool, from ivory and beige to gray and black. Generally, a Two Grey Hills weaving has a border, four matching corner elements, and a large diamond-shaped centerpiece.

Thelma Brown is a fourth-generation weaver who helps carry the tradition forward. Brown first took up the craft in high school in the 1980s to help pay for yearbooks and her graduation cap and gown. When she began working at Toadlena, Winter helped Brown identify her family lineage of weaving and learn more about her great-grandmother’s and grandmother’s designs. Decades later, she still enjoys processing wool and the relaxed mood of weaving. “It’s soothing for me,” she says. “It’s like therapy working on wool and sitting at the loom in your own little world with your heddle, weaving fork, and dowel.”

Besides her family’s tradition, Brown also finds inspiration in the many designs that pass through the trading post. She chats with fellow weavers about their techniques and passes those along to weavers just beginning the art. She invites this new generation to call with questions or bring portable looms by the trading post for tips as a way to continue the area’s weaving legacy.

“Some weavers, I’ve been working with for years. But I’ve never spoken to them, because we don’t speak the same language,” Winter says of the elders who speak only the Navajo Diné language and have become their culture’s preservationists through language and heritage. Some of their art pieces represent eight months of full-time work, and a place like Toadlena is often the closest people come to buying from the weaver. (Other opportunities are available at events like the Crownpoint Navajo Rug Auction, usually held monthly.)

The elaborate designs of Two Grey Hills weavings reflect the regional style of Two Grey Hill of the Navajo Nation, just as other regions of the Navajo Nation use specific colors and patterns for their area. Driving through its 27,000 square miles, your GPS will often steer you wrong, washboard roads await, and many travelers are drawn into the stunning settings. Pine trees edge red rolling hills, buttes spring from the desert floor, and open mesas stretch to the horizon.

Great for families and outdoor enthusiasts, the Bowl Canyon Navajo Recreation Area serves as the gateway to the Chuska Mountains and offers picnicking, camping, canoeing, and fishing surrounded by cool pines, scenic views, and red sandstone formations. About 11 miles east of Navajo, Camp Asááyi, pronounced (Ah-saa-yeh), sits at 7,528 feet and provides a bounty of activities.

- Admission Fee $10/day/vehicle.

- Navajo Nation Fishing License Required

- Day Use only 8am to 4:30pm.

To connect with this desertscape and the Diné way of life, begin in the far northwest corner of New Mexico, near the town of Nageezi. Chaco Culture National Historical Park, managed by the National Park Service, protects Ancestral Puebloan great houses that were once a center of the ancient world. The structures provide insight into some of heritage cultures of the Southwest, though these peoples had a different lineage than the Diné who now surround it.

Cruising toward Farmington, the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness Area features fantastical hikes. In the Diné language, Bisti is known as “a large area of shale hills”—a fitting description for a moonscape where wind and water have eroded the sandstone into pinnacles, spires, and giant egg-like shapes. De-Na-Zin, meaning “cranes,” has a similarly austere landscape. Navajo Tours USA offers outings to Bisti and Chaco, with Native guides sharing about their culture.

Visitors may also drive by the Shiprock Pinnacle, located 15 miles southwest of the town of Shiprock. The towering volcanic formation juts from the desert floor and is known in Diné as “Rock with Wings.” On the farthest northwestern edge of the New Mexico state line, travelers can stand in four states at the same time at the Four Corners Monument, where Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet. Looping south, visitors can end their two- to three-day journey at Toadlena, with a souvenir weaving to remember their trip by.